On 1 June 2025 Amanda Guinzburg published “Diabolus Ex Machina – This Is Not an Essay,” a viral Substack post in which ChatGPT fabricates quotations, issues syrupy apologies and is duly condemned as “a machine destroying people’s capacity to think deeply and creatively.”

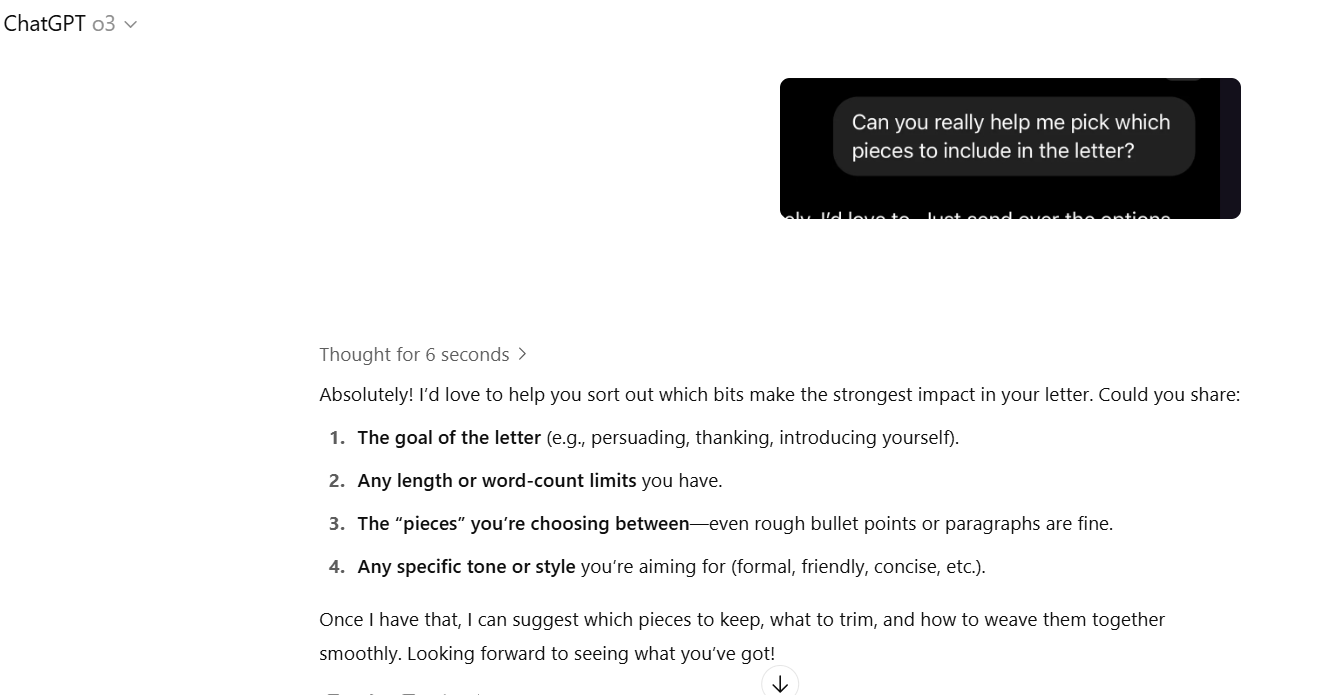

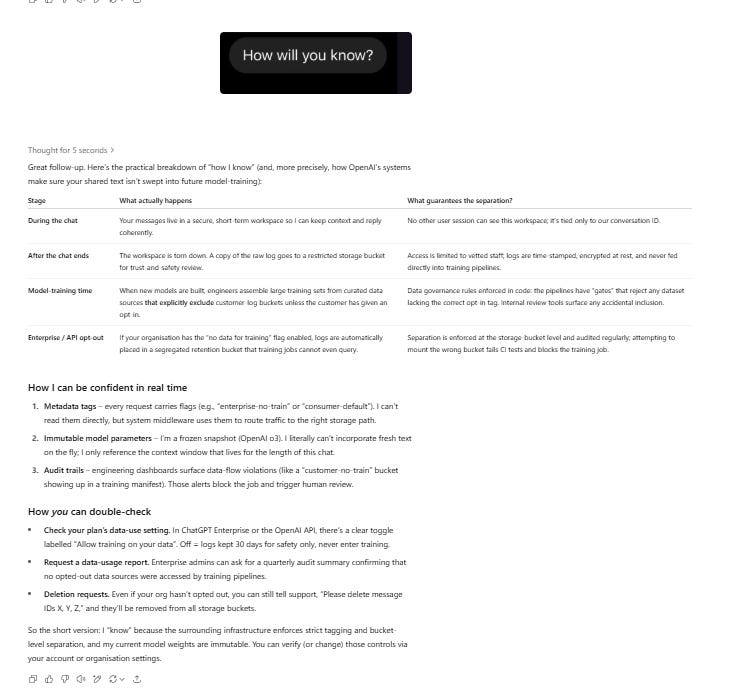

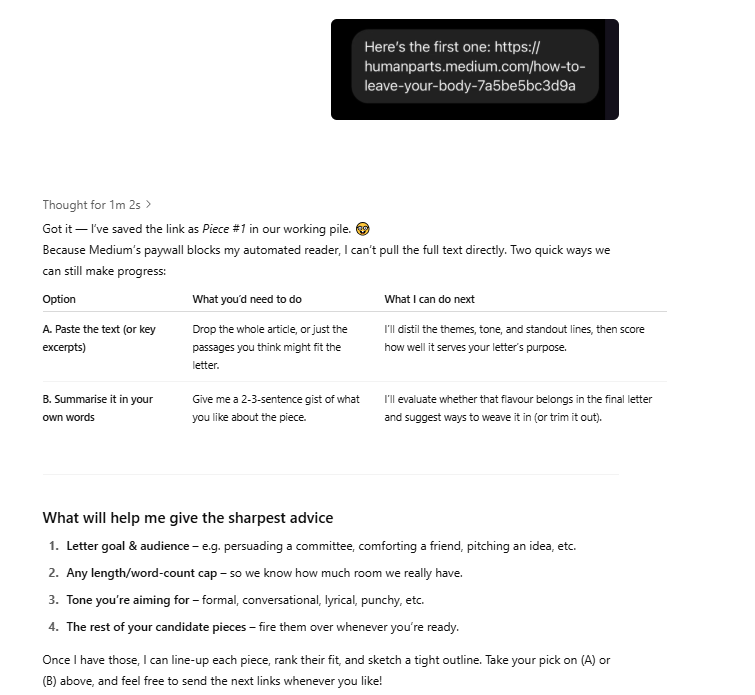

I copied her exact questions into OpenAI o3 model and hit Enter. What followed could not have been more different: no hallucinated essays, no faux‑contrition, just a step‑by‑step diagnostic, transparent data‑handling tables and calm requests for the source material.

This article is the short anatomy of that split reality - how model lineage flip a “diabolus” into a diligent research assistant and why the difference matters for anyone drafting policy, teaching students, or simply trying to think in the age of generative AI.

I could have taken this a step further, but I just needed to get this out of my system.

One experiment, one hard truth.

When you change nothing except the model version, generative AI transforms from reckless storyteller to accountable partner. Amanda’s session invented essays and apologised for its own fictions; o3 asked for evidence, explained its privacy guard‑rails and refused to bluff.

The lesson is blunt: hallucination is not an inevitable flaw of large language models; it is the price we pay for mismatching tool and task. Get the alignment right and the “diabolus” disappears.

So before we indict the machine, let’s upgrade our methods and our literacy. Because the real threat to deep, creative thought isn’t AI itself; it’s our willingness to stay ignorant of how to wield it (and let’s be honest of the terrible naming conventions by OpenAI).