Inside the University of 2030?

The Settled Revolution

This piece is design fiction, a walk‑through of a university that has chosen to put the human at the centre with AI as a powerful partner. It isn’t a prediction, a policy blueprint, or a hill to die on. Some elements are already peeking into reality; others are deliberately aspirational; a few may never arrive. Universities are behemoths. That’s precisely why fiction helps: it gives us a safe, vivid space to rehearse choices, surface trade‑offs, and ask better questions before we harden systems.

Think of this Substack as my studio for thinking aloud about human/AI relationships, NOT a set of truths I need to defend. If a scene feels implausible, treat it as a prompt: what would have to be true for this to work and what would we refuse to trade away? If a passage feels uncomfortably real, use it to name the values and practices we won’t outsource.

With that spirit of exploration, step into 2030, then step back with me to decide what we actually want to build.

Standing in the central atrium of any major university in 2030, you witness a peculiar harmony. Students move through spaces that feel both timeless and radically new, carrying themselves with a confidence that would have seemed impossible during the turbulent years of AI’s initial disruption. The panic has passed. The adaptation is happening. What emerged from five years of fundamental reimagining is not the apocalypse many predicted, nor the techno‑utopia others promised, but something more interesting: an institution that finally knows what it’s for. In an age of intelligent machines, the university’s most defensible value is the cultivation of uniquely human skills.

The transformation is visible in the smallest details. Watch a student working in the library, constructing what her programme calls a knowledge architecture for her capstone on urban sustainability. Her AI research orchestrator running atop the campus knowledge graph and the compute infrastructure of Project Stargate, which came online in phases after its 2025 announcement, has already synthesised 4,000 papers published in the last twelve months alone. It identified seven contradictory frameworks and mapped the conceptual terrain with a precision no human could achieve. But watch what she does with this foundation. She challenges core assumptions, discovers a bias in how South Asian cities were categorised and identifies a gap where Indigenous planning principles have been systematically overlooked. A Knowledge Steward, today’s librarian has pre‑vetted the corpus, tuned retrieval to reduce cultural skew, and built a provenance layer so every citation is auditable. Her professor, who meets with her every week, doesn’t teach her facts. He teaches her how to interrogate systems, how to spot what’s missing, how to know when the AI is reproducing rather than thinking.

This is the profound shift that occurred somewhere around 2027: universities stopped trying to compete with AI and started teaching students to transcend it. The phrase “cognitive sovereignty,” coined by researchers at MIT, became the organising principle. Students aren’t protected from AI; they’re immersed in it. Every course now includes what’s formally called Epistemic Foundations but what students simply call thinking about thinking. They learn not just to use AI but to understand its architecture of knowledge, its inherited assumptions, its failure modes. They develop what one educator calls intellectual proprioception, an intuitive sense of where their thinking ends and the machine’s begins, and how to reclaim it when it starts to blur.

The day begins differently for students now. Marcus, a second‑year studying what his university calls Integrated Systems and Philosophy, starts his morning in what would have been unimaginable five years ago: a mandatory cognitive gymnasium session. For ninety minutes, no devices, no AI, just Marcus and eleven others wrestling with a paradox their professor has posed about consciousness and measurement. They diagram on whiteboards, argue, get frustrated, break through, argue again. The professor offers no answers, only better questions. This isn’t a return to pre‑digital education; it’s something new. These students can summon vast computational power at will, but they’ve also developed what researchers call naked cognition, the ability to think deeply without augmentation. They’re cognitively ambidextrous in a way no previous generation has been: fluent at orchestrating AI when it helps, disciplined at bracketing it when it harms understanding.

The architecture of assessment has been completely reimagined. The old binary of “aided” versus “unaided” work proved too simplistic. Instead, universities developed what’s now the standard cognitive attribution system. Every piece of work students submit includes what educators call a thought chain, a detailed map of which insights came from the student, which from AI collaboration, which from peer discussion and which from faculty guidance. Behind the scenes lives a provenance ledger: version trails, virtual chat histories with insights, journals, dataset links and oral‑defence recordings that together make learning transparent. The policy is no longer “Did you use AI?” but “Did you declare your tools?” Hiding AI use has become the new plagiarism. A typical assignment might require students to use AI to generate five different approaches to a problem, then write a critical analysis of why four of them fail, then defend their chosen approach in a live oral examination where professors test not their memory but their reasoning and cross‑check it against the attribution ledger.

The oral examination, or viva, has experienced a remarkable renaissance. Once relegated to doctoral defences, vivas are now woven throughout undergraduate education. But these aren’t the intimidating interrogations of Oxford tradition. They’re dynamic conversations where students demonstrate not what they know but how they think. Professor Chen, who teaches in what her university calls the School of Augmented Humanities, conducts three vivas every afternoon. She describes them as “intellectual jazz sessions”, structured enough to evaluate competence but improvisational enough to reveal genuine understanding. Students can’t prepare prefab answers because the questions emerge from the conversation itself. They can’t hide behind AI‑generated eloquence because they must think aloud, in real time, with another human who probes for gaps, invites doubt and asks the question the model didn’t.

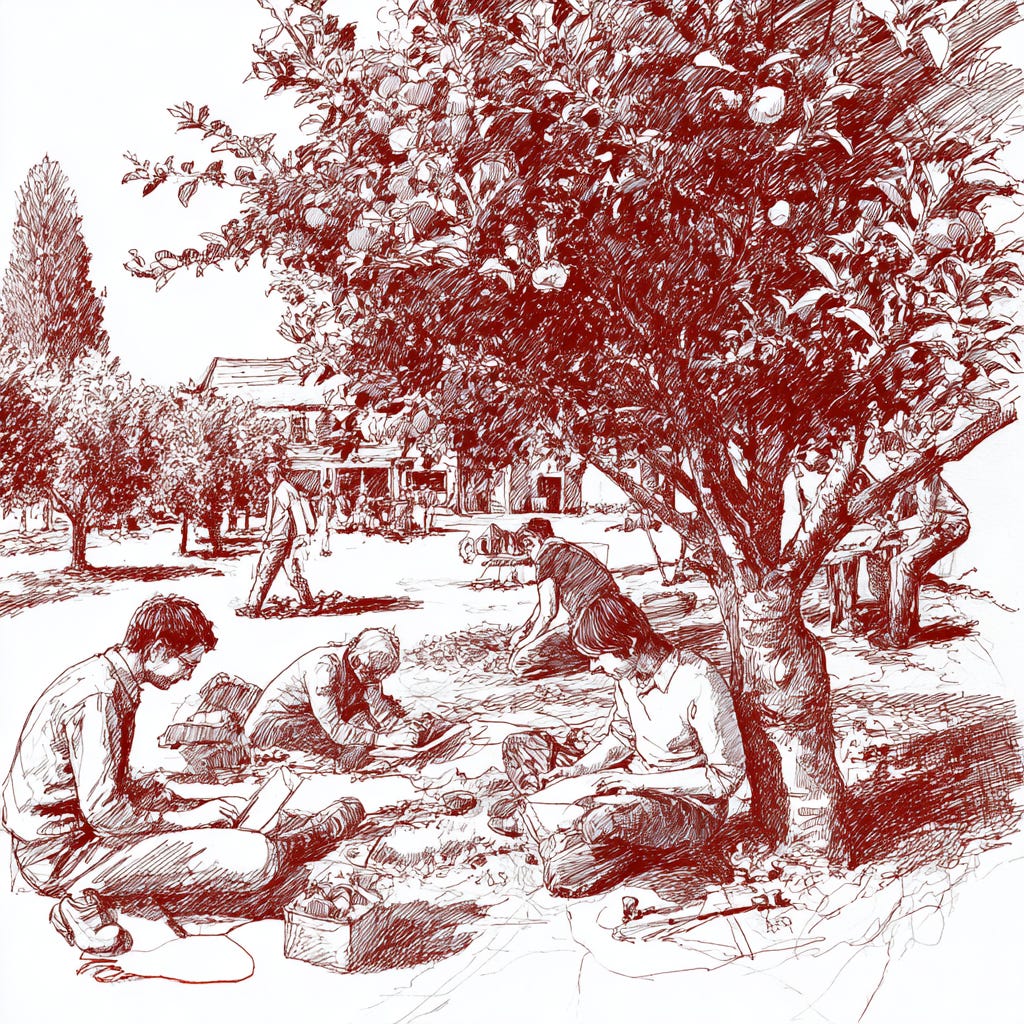

The physical campus has been radically reconceived around this new educational philosophy. The dominant architectural form is what designers call collaborative studios, flexible spaces that can shift from solitary deep work to small‑group collaboration to full seminar within minutes. Deliberately, consciously, these spaces also include friction zones areas where technology is limited or absent entirely. The university discovered, through painful trial and error, that learning requires what cognitive scientists call desirable difficulties or productive struggle. Too much ease breeds superficial understanding. So they built difficulty back into the system, deliberately, strategically, not as limitation but as pedagogical design. Accessibility is not an afterthought: universal design is standard and AI‑driven captioning, reading supports, and adaptive interfaces are available, but with clear digital boundaries so supports don’t become cognitive crutches.

Faculty roles have crystallised into new but stable patterns. The feared mass unemployment never materialised; instead, academic work specialised and intensified in a process of disaggregation. Dr Rodriguez exemplifies the new model. Officially, she’s a Learning Experience Architect, one of several specialised roles that also include Assessment Architects, High‑Empathy Coaches and Knowledge Engineers working alongside librarians. Her students simply call her their cognitive coach. She designs elaborate learning journeys that weave together AI instruction, peer collaboration, hands‑on experimentation and philosophical reflection. She meets each of her students individually monthly, tracking their intellectual development rather than their knowledge acquisition, which AI handles. She knows which students tend toward over‑reliance on AI, which resist it and which haven’t yet developed their own voice. Her expertise isn’t in transmitting information but in recognising and nurturing the emergence of independent thought and in governing tool use: choosing which models are valuable, what data they may touch and when the friction zone applies.

The relationship between students and AI has evolved into something more nuanced than early observers predicted. Yes, every student has what they call their cognitive partner, an AI that knows their academic history, learning patterns, strengths, and struggles. These AI tutors- powered by GPT‑7’s real‑time learning capabilities that began rolling out in 2028 and built on GPT‑6’s persistent memory in 2026, don’t just respond; they anticipate confusion, suggest connections, and sometimes deliberately introduce productive mistakes to test understanding. Confidence scores and explainable rationales are now standard UI so students can see when the model is ‘guessing’. But students have also developed sophisticated scepticism. They’ve learned prompt literacy, not just how to get good answers from AI but how to recognise creative approaches. They play what one student describes as “intellectual chess” with their AI tutors, using them as sparring partners rather than oracles, drawing lines between delegation and judgment and knowing when to switch from augmented to naked cognition.

The curriculum has reorganised around what educators now call durable human skills rather than traditional siloed disciplines. A typical programme combines elements that would have been scattered across a dozen departments in 2024. Sarah, a third‑year student, is pursuing what her university calls a Constellation Degree in Ethical Systems and Emergence. Her morning might include a seminar on moral philosophy, followed by a lab where she programmes AI agents to model social cooperation, then an afternoon workshop where she analyses algorithmic‑bias case studies with students from law, computer science, and sociology. The boundaries between disciplines haven’t disappeared, but they’ve become permeable. Knowledge is organised around problems rather than traditions and every pathway includes AI literacy, data ethics and epistemic humility as core threads.

This interdisciplinary approach emerged from necessity. When AI can instantly access and synthesise knowledge from any field, the value of human education shifted toward what researchers call interstitial intelligence, the ability to work in the spaces between established domains. Universities discovered their graduates’ greatest contribution wasn’t deep expertise where AI already exceeds them, but the capacity to work across fields, to spot what computer scientists call edge cases where established knowledge fails, and to ask questions that haven’t been asked. The library’s knowledge stewards curate cross‑disciplinary corpora and align ontologies so those interstices are navigable rather than nebulous.

The credentialing system has evolved into something unrecognisable from the diplomas of even five years ago. Students graduate with what universities call a competency constellation, a dynamic, verified record of specific capabilities that updates throughout their lives. This is part of a national shift toward portable skills passports (verifiable digital credentials). Emma, graduating this year, doesn’t receive a static bachelor’s degree in biology. Her credential is a living document that specifies thirty‑seven validated competencies ranging from advanced biological systems modelling to ethical reasoning in genetic intervention to cross‑cultural science communication. Each competency includes not just a grade but evidence: recordings of oral examinations, documented project processes, peer evaluations and cognitive attribution chains showing how she integrates AI assistance with independent thought. Employers in 2030 value this granular proof of skill, by the late 2020s many hiring systems could ingest these credentials directly.

But perhaps the most profound transformation is in what students are learning to value. The early fear that AI would make students intellectually lazy proved both right and wrong. Yes, the initial years saw what researchers called cognitive atrophy as students off‑loaded too much thinking to machines. But by 2028, a cultural shift occurred. Students began to take pride in what they could do without AI, viewing it as a mark of distinction. Raw cognition became a status symbol. Student clubs formed around analogue thinking, solving problems using only what one educator calls “stone‑age tools”: paper, pencil, and the human mind. These aren’t luddites rejecting technology but sophisticated users choosing when to engage and when to abstain, practising the discernment that makes augmentation safe and meaningful.

The social dynamics of learning have intensified rather than diminished. The prediction that education would become solitary and screen‑mediated proved entirely wrong. Instead, the campus of 2030 thrums with more human interaction than ever. Study groups aren’t optional extras but required components of most courses. The university discovered that when individual cognitive tasks can be automated, collaboration, communication, conflict resolution and collective creativity become the core curriculum. Every student participates in what educators call cognitive teams, small groups that work together throughout their university years, learning not just from AI and faculty but from the friction and synergy of human difference. These teams maintain team attribution ledgers and practise group vivas, making collective thinking visible and accountable.

Mental‑health support has been completely reimagined. The initial crisis, when some students formed unhealthy dependencies on AI companions, which had become their “third place” for advice, forced universities to develop what they now call relationship ecology programmes. Every student learns to map their relationships with AI, with peers, with faculty, and with themselves. They’re taught to recognise what psychologists term parasocial drift, when AI relationships begin substituting for human ones, and how to maintain what counsellors call emotional biodiversity. AI companions aren’t banned, but the platforms now signal confidence, uncertainty and boundaries, and students are coached to set digital curfews and cultivate offline anchors, rituals and communities that keep them humanly connected.

The economics of this transformation stabilised in ways few predicted. The sector stratified into distinct models. Yes, some universities pursued the fully Automated model, delivering education at massive scale through AI “super‑tutors.” Others became boutique Human‑Centric institutions selling high‑touch, in‑person experiences at a premium. But most, like this one, found a middle path economists call progressive personalisation, an Augmented University model that blends the best of both. Foundational cognitive skills are taught efficiently through AI, lowering cost‑of‑delivery and making quality education affordable at scale. As students advance, human involvement increases. By their final year, students spend most of their time in small seminars, intensive mentorship, and collaborative projects. The model isn’t cheap, but it’s sustainable, funded through a combination of tuition, corporate partnerships, and lifetime learning subscriptions, where alumni pay an annual fee for continued access to AI tutors, Studio resources, and periodic human instruction. Sustainability isn’t only financial: the campus has invested in green compute and compute‑aware scheduling to reduce the energy footprint of always‑on AI.

The feared great unbundling of higher education happened, but not as anyone expected. Yes, students can now earn micro‑credentials from multiple providers. Rather than destroying the university, this forced institutions to clarify their unique value. Universities positioned themselves as cognitive orchestrators, the only institutions capable of weaving disparate learning experiences into coherent intellectual development. They became not providers of content but architects of transformation. A student might learn coding from an online platform, ethics from a philosophy professor, and project management from a corporate programme, but the university provides the framework, the library, the attribution ledger, the viva culture that transforms scattered competencies into wisdom.

Research has transformed perhaps most radically of all. The feared obsolescence of human researchers never materialised, but their role changed completely. Dr Park, who leads a research group in what her university calls Emergent Systems Biology, describes her work as “conducting an orchestra of minds.” Her team includes three human postdocs, seventeen AI research agents, and a cognitive synthesis engine that continuously integrates findings across all of them. The humans don’t do brute‑force calculations or exhaustive literature reviews; AI handles that instantly. Instead, they do what Dr Park calls meaning‑making: identifying which questions matter, recognising when results are significant versus merely statistically significant, and most importantly, maintaining ethical oversight of research directions. All AI assistance is meticulously disclosed in an AI Contributions section of their publications, a standard adopted by major journals around 2027. Raw data, code, and model cards are archived in the Studio with tamper‑evident provenance, making reproducibility a default rather than an aspiration.

The campus at twilight reveals the transformation most clearly. In the collaborative studios, students work in what observers describe as a cognitive ballet, seamlessly moving between AI consultation, peer discussion, solitary reflection, and group synthesis. In the friction zones, others engage in what looks almost medieval: intense, technology‑free dialogue about fundamental questions. In the research labs, human and artificial intelligence interweave so completely that identifying where one ends and the other begins becomes both impossible and irrelevant, because provenance, purpose, and ethics remain clearly human‑owned.

The faculty lounge, that endangered space, hasn’t disappeared but transformed. Professors gather not to complain about students or technology but to engage in what they call pedagogical jazz, improvisational sessions where they design new learning experiences, share breakthrough moments, and debug failed experiments. They’re not the sage on the stage or even the guide on the side but something new: intellectual choreographers, designing dances between human and artificial intelligence that somehow, improbably, produce genuine learning.

The class of 2030 graduates into a world where the feared “AI replacement” never quite happened, but neither did the promised “AI augmentation” in any simple sense. Instead, they enter what economists call the cognitive economy, where value comes not from knowing things or even from thinking things but from what one researcher terms cognitive arbitrage: recognising the gaps between different forms of intelligence and bridging them creatively. They’re prepared not for specific jobs, most of those will transform within years, but for what educators call perpetual adaptation. They’ve learned not subjects but meta‑subjects: how to learn, how to think, how to collaborate, and how to remain human while working with increasingly powerful artificial minds.

The university of 2030 succeeded not by resisting AI or embracing it uncritically but by doing something more subtle and difficult: maintaining creative tension. Every aspect of education now exists in productive dialogue between human and artificial intelligence. Not balance (that implies stasis) but dialogue (which implies growth). Students learn with AI and without it, through AI and despite it, because of AI and in conscious opposition to it. They develop what philosophers call cognitive plurality, the ability to think in multiple modes without losing their own intellectual identity.

This isn’t the future many predicted in the panicked years of 2024 and 2025. It’s neither utopia nor dystopia but something more interesting: a working synthesis. The university didn’t die or become unrecognisable. It became more itself more focused on human development, more conscious of its purposes, more deliberate in its methods. The crisis of AI forced higher education to answer questions it had avoided for decades: What is education for? What makes learning valuable? What distinguishes human intelligence? The answers emerged not from theory but from practice; not from planning but from experimentation; not from resistance but from creative adaptation.

As night falls on the campus of 2030, the last seminars conclude, the labs power down, the studios empty. But learning continues: AI tutors work with students across time zones, research agents pursue hypotheses through the night. Tomorrow, students will return to wrestle again with the central challenge of their education: not to compete with artificial intelligence or surrender to it, but to find their own irreducible humanity in dialogue with it. The university of 2030 has become what it was always meant to be but rarely achieved: a place where humans discover not just what they can know but who they can become.

The real work has just begun.

Absolutely brilliant. Hands down one of the best expressions of what education could be in the future. Has to be. Actually, no, it’s the best one I have read (and as a teacher I read ALLL the things.)

Hybridity but with clear delineation? As someone who works education and understands hybridity as a lived experience of self, I totally get and fully applaud this vision.

What’s more, we have begun the work in my school with both careful AI adoption AND a focus on oracy. It’s possible, and we are taking steps towards this already.

This is awesome!